Using residential-grade valves in an industrial facility isn’t a cost-saving measure; it’s a direct route to premature failure, regulatory non-compliance in Quebec, and exponential long-term costs.

- Component failure is often systemic, stemming from a mismatch in pressure ratings (Class), material science (chemical/thermal resistance), and system dynamics (water hammer).

- In Quebec, installing non-compliant pressure equipment (lacking a valid CRN) is illegal and poses significant liability risks under RBQ and CNESST regulations.

Recommendation: Immediately shift your component selection criteria from initial purchase price to a rigorous analysis of Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), system integrity, and mandatory Quebec regulatory compliance.

You’ve seen it before. A valve that was replaced just six months ago is already weeping, seizing, or failing outright. Your maintenance team is frustrated, production is halted, and you’re left questioning the quality of the components. The typical response is to blame the manufacturer or the installation, but the root cause is often far more fundamental and strategic: a residential-grade component has been forced into a demanding industrial role it was never designed to survive. This isn’t just a minor technical error; it’s a costly blind spot for many facility managers.

The temptation to choose a cheaper, seemingly equivalent part from a big-box supplier is understandable, especially when facing tight budgets. The common wisdom suggests a valve is just a valve. However, this perspective ignores the harsh realities of industrial environments: extreme pressures, corrosive chemicals, high temperatures, and violent hydraulic shocks. More critically, especially in a regulated jurisdiction like Quebec, it overlooks a web of legal requirements overseen by bodies like the Régie du bâtiment du Québec (RBQ) and the CNESST.

The real key to reliability and long-term cost savings isn’t finding a cheaper valve; it’s understanding why the industrial-grade component is the only viable option. The initial higher price tag is not an expense but an investment in safety, compliance, and operational continuity. This article will deconstruct the catastrophic failures that occur when this principle is ignored. We will move beyond the superficial “use the right part” advice to explore the specific mechanical, chemical, and legal reasons residential valves are doomed to fail in your facility, providing a clear framework for making decisions that protect your assets, your people, and your bottom line.

To fully grasp the risks involved and build a robust component strategy, we will explore the critical distinctions between residential and industrial hardware across several key areas. The following sections break down the most common and costly failure points, offering a clear roadmap for ensuring reliability and compliance within your Quebec facility.

Summary: Decoding Valve Failure: A Manager’s Guide to Industrial-Grade Components

- Classe 150 vs Classe 300 : comment lire les brides pour éviter l’explosion ?

- Joints EPDM ou Viton : lequel résiste aux produits chimiques de nettoyage industriel ?

- Numéro d’enregistrement canadien (NEC) : pourquoi est-ce illégal d’installer une cuve sans ce numéro ?

- Amortisseurs de coups de bélier : comment protéger vos pompes contre les fermetures brusques de vannes ?

- Standardisation des pièces : pourquoi utiliser une seule marque de vanne réduit vos temps d’arrêt ?

- Pourquoi l’eau bouillante détruit-elle les drains standards en PVC en quelques mois ?

- Coût cycle de vie : comment l’inox devient moins cher que le plastique après 10 ans ?

- Why Are Gate Valves Critical for Lockout-Tagout Procedures in Quebec?

Class 150 vs. Class 300: How to Read Flanges to Prevent Explosions

One of the most dangerous and common mistakes is mismatching flange pressure ratings. A residential valve might look physically similar to an industrial one, but the embossed markings on its flange tell a story of immense difference in capability. These markings, governed by standards like ASME B16.5, are not suggestions; they are safety-critical specifications. The “Class” rating (e.g., 150, 300, 600) defines a flange’s ability to withstand a specific pressure at a specific temperature. It’s not a single pressure value but a curve.

A Class 150 flange, common in residential or light commercial plumbing, might be rated for around 285 psig at ambient temperatures. A Class 300 flange, however, can handle approximately 740 psig under the same conditions. Installing a Class 150 valve in a Class 300 system creates a catastrophic weak point. As process temperatures rise, the pressure-holding capacity of all flanges decreases. The residential-grade flange will fail long before its industrial counterpart, leading to gasket blowouts, hazardous leaks, or even explosive disassembly.

Reading these markings is a fundamental skill for ensuring plant safety. The flange will have its size, pressure class, material specification, and manufacturer stamped directly onto its edge. Ignoring these details is equivalent to disabling a safety relief valve—it turns a predictable system into a time bomb. For a facility manager, ensuring that every component matches the system’s designated pressure class is a non-negotiable first line of defense against catastrophic failure.

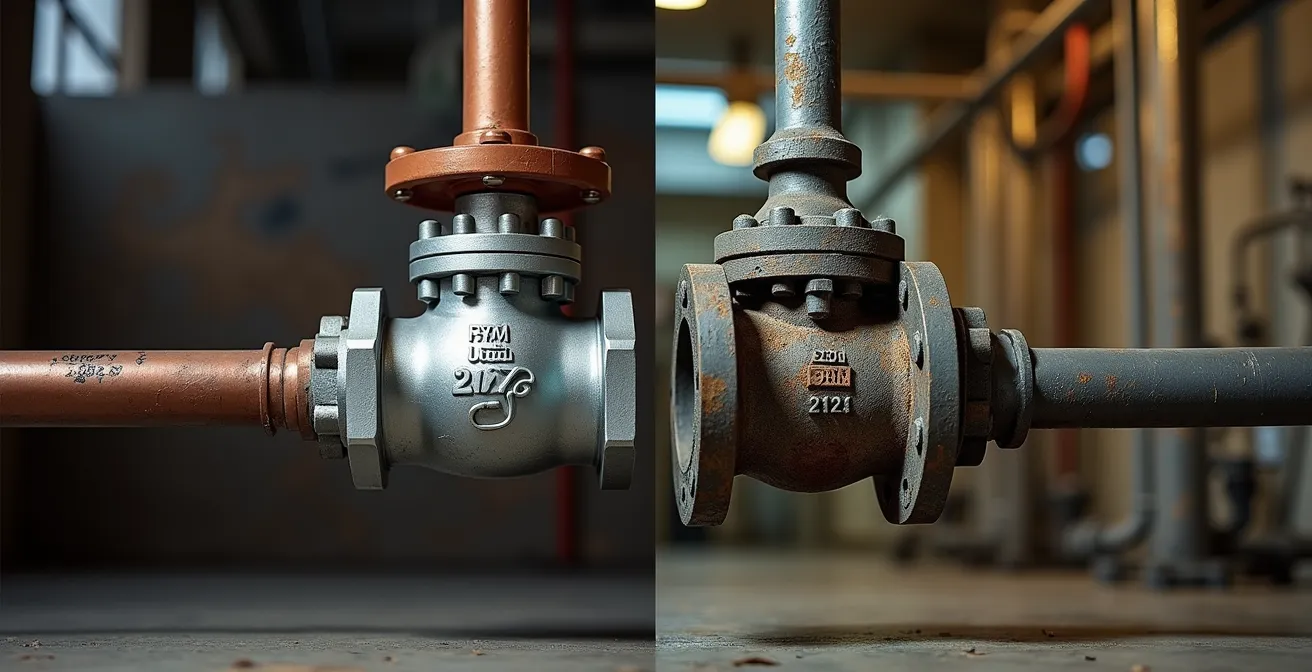

The intricate markings on an industrial flange, as seen in this close-up, are the component’s resume. They communicate its pressure class, material, and compliance, information that is essential for safe operation and is completely absent or insufficient on residential-grade hardware.

EPDM vs. Viton Gaskets: Which Resists Industrial Cleaning Chemicals?

A valve is only as strong as its softest parts, and in industrial applications, gaskets are a primary point of failure. While a residential valve might use a basic rubber or EPDM gasket suitable for potable water, industrial processes, especially in food and beverage, involve aggressive Clean-in-Place (CIP) chemicals. Caustics, acids, and sanitizers used in CIP cycles will rapidly degrade incorrect gasket materials, leading to leaks, contamination, and costly downtime.

The two most common elastomers, EPDM (Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer) and Viton (a brand of FKM), have vastly different chemical resistances. EPDM is excellent for water and steam but performs poorly when exposed to fats, oils, and many hydrocarbon-based solvents. Viton, while more expensive, offers superior resistance to a broad spectrum of chemicals, including the fatty acids and aggressive cleaning agents common in food processing, and can withstand higher temperatures. Choosing a valve with an EPDM seal for a process involving fatty products or harsh CIP cycles is guaranteeing its failure.

The decision must be based on a chemical compatibility analysis of your specific process fluids and cleaning protocols. This table, based on data from industrial valve failure analyses, highlights the critical differences for a Quebec food industry context.

| Property | EPDM | Viton |

|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acids Resistance | Poor | Excellent |

| CIP Chemical Compatibility | Limited | Superior |

| Temperature Range | -40°C to 150°C | -26°C to 230°C |

| FDA Compliance | Available | Available |

| Cost for Quebec Suppliers | Lower | Higher |

As the comparison shows, while EPDM is cheaper, its poor performance with fats and limited chemical compatibility make Viton the only logical choice for many demanding applications. Investing in the correct gasket material from the start prevents product contamination, protects downstream equipment, and eliminates frequent replacement cycles.

Canadian Registration Number (CRN): Why Installing a Vessel Without It Is Illegal

Beyond technical failure, installing the wrong component in Quebec can put your facility in direct violation of the law. Any pressure vessel, fitting, or valve intended for use above 15 psig must have a Canadian Registration Number (CRN). This number signifies that the component’s design has been reviewed and registered by the technical safety authority of a Canadian province or territory. For Quebec, this authority is the Régie du bâtiment du Québec (RBQ).

Residential valves, sold through general hardware channels, almost never have a CRN. They are not designed or registered for pressurized industrial service. Installing one in a regulated system is illegal and voids any insurance coverage related to its failure. This creates a massive liability for the facility manager and the company. Inspectors from the RBQ or auditors from the CNESST can order the immediate shutdown of non-compliant systems, resulting in crippling production losses.

Furthermore, the process is not as simple as finding any part with a CRN. As the Régie du bâtiment du Québec makes clear, the registration must be specific to the province of installation. In their official guidance, the RBQ states:

A CRN from another province is not automatically valid in Quebec without RBQ validation

– Régie du bâtiment du Québec, Provincial CRN Requirements Guide

This critical detail means you must actively verify that the CRN on your equipment is registered and valid *in Quebec*. Assuming a CRN from Ontario or Alberta is sufficient can lead to the same non-compliance penalties. For any new equipment, demanding a Quebec-valid CRN from your supplier is an essential step in your procurement process. Verifying this number is a straightforward but non-negotiable task.

Your CRN Verification Checklist for Quebec Facilities

- Locate the CRN marking on your pressure vessel or fitting (it typically starts with a letter, followed by numbers, and ends with a provincial code like “.6” for Quebec).

- Access the RBQ’s public registry database to search for the number.

- Verify that the CRN is actively registered specifically for use in Quebec.

- Check for any expiry date or limitations on the scope of the registration.

- Document the verification in your compliance and maintenance records for audit purposes.

- For all new equipment purchases, make a Quebec-specific CRN a mandatory requirement on your purchase order.

Water Hammer Arrestors: Protecting Pumps from Sudden Valve Closures

Valve failure isn’t always a slow leak; it can be the cause of a system-wide catastrophic event known as water hammer (or hydraulic shock). This occurs when a fluid in motion is forced to stop or change direction suddenly, such as when a fast-closing residential ball valve is slammed shut. The momentum of the entire fluid column is converted into a massive pressure spike that travels back through the piping at the speed of sound.

This pressure wave can be immensely powerful, easily exceeding the pressure rating of pipes, fittings, and especially pumps. The kinetic energy involved is staggering; calculations for hydroelectric facilities show that the water in a long tunnel can contain immense energy, sometimes in the range of 8,000 megajoules in a 14km tunnel. While a factory system is smaller, the principle is identical. This shockwave can rupture pipe seams, destroy pump impellers, and cause valve bonnets to fail violently. Residential quarter-turn ball valves are particularly notorious for causing water hammer because they can be closed almost instantaneously, unlike industrial-grade, slow-closing gate or globe valves equipped with geared handwheels.

To prevent this, industrial systems are designed with water hammer arrestors. These devices contain a pocket of compressible gas (like nitrogen) behind a piston or diaphragm. When a pressure spike occurs, the gas compresses, absorbing the shockwave and protecting the system. As a basic form of this, some large-scale systems use a surge shaft, a vertical pipe that allows water to flow upwards, converting kinetic energy into potential energy safely. Installing a residential valve without considering the system’s dynamics is inviting a destructive water hammer event that will cause far more damage than the cost of the valve itself.

Parts Standardization: Why a Single Valve Brand Reduces Downtime

Walking through a facility with a patchwork of different valve brands, models, and types is a maintenance nightmare. This often results from chasing the lowest price on individual purchases, a classic symptom of a residential, commodity-based procurement mindset. The consequence is a bloated spare parts inventory, increased training complexity for maintenance staff, and significantly longer mean time to repair (MTTR). Industrial best practice, in contrast, is built on standardization.

By standardizing on a single, high-quality industrial valve brand and model for specific applications, you create a streamlined and resilient system. Your spare parts inventory shrinks dramatically; instead of stocking dozens of different repair kits, seats, and seals, you only need a few. Your maintenance team becomes expert-level technicians on that specific hardware, able to diagnose and repair issues in minutes rather than hours. According to industry maintenance data, industrial valves may require attention, but a standardized approach means that when a repair is needed, typically within 3-5 years for some components, the process is efficient and predictable.

The hidden costs of a mixed-brand environment are substantial. Diagnostic time increases as technicians must first identify the valve and then find the correct manual and parts. Ordering a unique part, especially for remote regions in Quebec, can take days or weeks, leaving a critical production line idle. Furthermore, managing CRN compliance becomes a complex spreadsheet exercise instead of a simple check. A standardized inventory of pre-approved, CRN-compliant industrial valves simplifies compliance, maintenance, and inventory management, directly reducing operational costs and maximizing uptime. The small premium paid for a standardized, industrial-grade valve is easily recouped in the first maintenance cycle.

Why Boiling Water Destroys Standard PVC Drains in Months

A frequent point of failure in food service or processing facilities is the drainage system. It’s common to see standard Schedule 40 PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) piping used for drains, as it is inexpensive and readily available. However, these drains are often subjected to intermittent discharges of hot water from commercial dishwashers, steam kettles, or equipment sanitation cycles. This is a recipe for rapid failure.

Standard PVC has a maximum recommended operating temperature of around 60°C (140°F). Above this temperature, the material begins to soften, sag, and deform. It loses its structural integrity, causing joints to leak and pipes to collapse over time. This isn’t a theoretical risk; it’s a certainty. As noted by engineering standards that inform plumbing codes, the danger is persistent. The National Plumbing Code of Canada’s material guidelines reflect this reality, with experts confirming that problems arise even below boiling point.

Even water below boiling point from industrial dishwashers causes standard Schedule 40 PVC to sag and deform over time

– National Plumbing Code of Canada, Material Requirements for Hot Water Drainage

The correct material for hot water drainage is either CPVC (Chlorinated Polyvinyl Chloride), which can handle temperatures up to about 93°C (200°F), or, for true industrial durability and temperatures exceeding boiling, stainless steel. The decision to use cheap PVC in a hot fluid application is a classic example of prioritizing initial cost over physical reality. The resulting leaks can cause water damage, create slip hazards (a major concern for CNESST), and lead to unsanitary conditions. The cost of replacing a failed PVC drain, including labor (Quebec plumber rates often range from $85-120/hour) and potential shutdown, will dwarf the initial savings many times over.

Key Takeaways

- The true cost of a component is its Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), not its initial purchase price. Factoring in downtime, labor, and replacement frequency reveals cheaper parts are far more expensive.

- In Quebec, compliance with RBQ and CNESST regulations, particularly the requirement for a valid Canadian Registration Number (CRN), is a legal and safety mandate that residential parts cannot meet.

- A single component choice impacts the entire system; a fast-closing residential valve can cause a water hammer event that destroys pumps and piping, demonstrating the need for a holistic, system-wide approach.

Lifecycle Cost: How Stainless Steel Becomes Cheaper Than Plastic After 10 Years

The most compelling argument against using cheap, residential-grade components is found by looking at the numbers. A Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) or Lifecycle Cost analysis shifts the focus from the initial capital expenditure (CapEx) to the long-term operational expenditure (OpEx). When you factor in the cost of replacements, labor, and—most importantly—lost production due to downtime, the “expensive” industrial-grade option is almost always cheaper.

Consider a simple comparison between a residential-grade PVC ball valve and an industrial-grade 316 stainless steel ball valve in a moderately demanding application. The PVC valve might fail annually, while the stainless steel valve could last a decade or more. The downtime associated with each failure is the real killer, often costing thousands of dollars per hour. Additionally, repeated failures can increase risk premiums with safety regulators like the CNESST.

This 10-year TCO analysis, based on data from valve maintenance specialists and typical Quebec labor rates, paints a stark picture.

| Cost Category | PVC Ball Valve | 316 SS Ball Valve |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Purchase | $150 | $450 |

| Failures (10 years) | 10 @ $150 each | 1 @ $450 |

| Labor (Quebec rates) | $9,000 | $900 |

| Production Downtime | $50,000 | $5,000 |

| CNESST Risk Premium | $10,000 | $2,000 |

| Scrap Value | -$50 disposal | +$100 recycling |

| Total 10-Year Cost | $70,700 | $8,250 |

The result is staggering. The “cheap” PVC valve ends up costing over 8 times more than the stainless steel alternative over a decade. A comprehensive total lifecycle analysis shows an 88% cost reduction with stainless steel in this scenario. This is the financial reality that must drive procurement decisions. As a facility manager, presenting a TCO analysis is the most powerful way to justify the investment in reliable, industrial-grade components to upper management.

Why Are Gate Valves Critical for Lockout-Tagout Procedures in Quebec?

Finally, the choice of valve type has direct implications for worker safety and compliance with Quebec’s stringent lockout-tagout (LOTO) regulations, known as cadenassage. The goal of LOTO is to bring equipment to a “zero energy state” before maintenance, ensuring that it cannot be accidentally re-energized. This is a core mandate of the CNESST under the *Loi sur la santé et la sécurité du travail (LSST)*.

For fluid systems, this means ensuring positive isolation—a guaranteed stop to the flow. This is where gate valves are superior to many other types, including the ball valves common in residential plumbing. An industrial gate valve with a rising stem provides unambiguous visual confirmation of its state. If the stem is up, the valve is open; if it’s down, it’s closed. This simple visual cue is a critical safety feature. Furthermore, they are designed to be fitted with robust locking mechanisms that meet CNESST standards. As the CNESST emphasizes in its guidelines on cadenassage:

Quebec’s LOTO (cadenassage) regulations, overseen by the CNESST, require a ‘zero energy state’

Many residential ball valves lack both the visual confirmation and a proper, built-in locking point. Attempting to lock out a simple lever-handle valve is often insecure and does not provide the positive isolation required. Using a non-LOTO compliant valve for energy isolation is a major safety violation. Gate valves, designed for on/off service and clear visual indication, are the industry standard for reliable cadenassage procedures, ensuring you meet your legal obligation to protect your workers. Choosing a cheaper valve can compromise your entire safety protocol.

The decision to use an industrial-grade component is not a luxury; it is a technical, financial, and legal necessity. By shifting the focus from short-term savings to long-term reliability and Total Cost of Ownership, you transform your facility’s maintenance from a reactive, costly firefight into a proactive, predictable, and safe operation. The first step towards achieving this is a critical audit of your existing systems. Evaluate your most frequently failing components against the principles of pressure rating, material compatibility, and regulatory compliance outlined here. This strategic approach is the foundation of a truly resilient and cost-effective industrial facility.