Mastering Quebec’s plumbing code is less about ticking compliance boxes and more about strategic asset management that ensures long-term operational resilience and cost control.

- High-durability fixtures and robust piping (like Type L copper) lower the total cost of ownership, despite higher initial outlays.

- Common “hygienic” solutions like electronic faucets can introduce unforeseen risks, such as Legionella contamination, requiring evidence-based selection.

Recommendation: Shift from a reactive, compliance-focused mindset to a proactive strategy that treats plumbing infrastructure as a critical factor in institutional performance and safety.

As a facility manager or maintenance engineer for a Quebec school or hospital, you live with the consequences of every pipe, valve, and fixture choice long after the architects and builders have left. The daily reality isn’t about abstract building codes; it’s about preventing a catastrophic flood in a patient ward, managing the relentless wear and tear from thousands of users, and justifying every dollar in a tightening budget. The common approach is to focus on meeting the minimum requirements of the Quebec Construction Code, Chapter III. But this is a defensive posture that misses the bigger picture.

The true challenge lies in navigating the operational and financial implications of these standards. We often hear about the need for “durable materials” or “hygienic design,” but these platitudes fail to address the core tension: how do you ensure absolute reliability and safety in a high-stakes environment while controlling a multi-decade total cost of ownership? The answer isn’t just in following the code, but in understanding its strategic intent. It’s about knowing why a specific type of copper pipe is mandated for hot water recirculation or what design flaws can render a universal bathroom non-compliant and legally vulnerable.

This guide moves beyond simple compliance. It reframes Quebec’s plumbing standards as a framework for building operational resilience. We will dissect the critical choices you face, from selecting seemingly indestructible toilets to designing maintenance plans that don’t crumble under budget cuts. We’ll explore the science behind material choices, the hidden risks in modern technology, and the protocols that safeguard human lives during an emergency. This is about making informed, strategic decisions that protect your institution, your budget, and the people you serve for years to come.

To help you navigate these critical decisions, this article breaks down the most pressing challenges and provides actionable, evidence-based solutions. The following sections detail the key standards and strategic considerations for building a truly resilient plumbing infrastructure in Quebec’s public institutions.

Summary: A Manager’s Guide to Institutional Plumbing in Quebec

- Institutional Toilets: How to Choose Indestructible Fixtures?

- Electronic Faucets: Are They Really More Hygienic and Economical?

- How to Organize a Maintenance Plan for 200 Bathrooms Without Blowing the Budget?

- Universal Bathrooms: The Design Flaws That Lead to Non-Compliance

- Hospital Water Outages: The Vital Protocol to Avoid Impacting Patient Care

- Round vs. Square-Bottom Drains: Which Prevents Bacterial Buildup?

- Water Velocity: Why Does Type L Copper Better Resist Turbulence Erosion?

- What Are the Plumbing Requirements for Food Processing Plants in Quebec?

Institutional Toilets: How to Choose Indestructible Fixtures?

In a school or hospital, a toilet is not just a fixture; it’s a high-frequency, high-abuse piece of critical infrastructure. The selection process must therefore prioritize long-term durability and total cost of ownership (TCO) over a low initial price tag. The goal is to specify equipment that can withstand decades of intensive use and intentional vandalism. This means looking for features like heavy-gauge stainless steel construction for security-risk areas or vitreous china with pressure-assist flushing systems for high-traffic public zones. These systems offer a powerful flush that clears the bowl effectively, reducing blockages and the need for frequent maintenance interventions.

Beyond material strength, water consumption is a major component of TCO. The institutional sector in Quebec is a significant water user, and specifying high-efficiency toilets (HETs) that meet or exceed code requirements is a financial imperative. According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, the combined commercial and institutional sector was responsible for a significant portion of water use, underscoring the impact of fixture choice at scale. When evaluating options, it’s crucial to assess not just the flush volume but also the fixture’s proven performance in preventing clogs, which can lead to costly emergency calls and water damage.

Ultimately, selecting an “indestructible” toilet is a strategic calculation. It involves balancing initial capital outlay with projected maintenance, water usage, and replacement costs over a 20- to 30-year lifespan. Engaging with CMMTQ-certified master plumbers during the specification phase is vital to ensure that the chosen fixtures are not only compliant with the Quebec Construction Code but also compatible with the building’s existing drainage infrastructure, particularly in older buildings with cast-iron systems.

Your Checklist for Selecting Institutional-Grade Fixtures

- Verify fixture compliance with all requirements outlined in Chapter III of the Quebec Construction Code.

- Consult with CMMTQ-certified master plumbers to confirm installation specifications and system compatibility.

- Compare the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), including water consumption rates and projected maintenance needs under Quebec standards.

- Ensure full compatibility with existing infrastructure, especially cast-iron drain, waste, and vent (DWV) systems.

- Factor in procurement lead times, especially when navigating public tender requirements for large-scale purchases.

This disciplined approach ensures that your investment delivers reliability and predictable costs, rather than becoming a recurring source of budget-draining emergencies.

Electronic Faucets: Are They Really More Hygienic and Economical?

The push toward touchless technology in public washrooms is driven by a powerful and intuitive idea: fewer touchpoints equal better hygiene. Electronic faucets are often marketed as a frontline defense against cross-contamination. However, for a hospital or school, where infection control is paramount, this assumption demands rigorous scrutiny. The internal complexity of these devices can, counter-intuitively, create new and significant hygiene risks. Their intricate network of solenoid valves, diaphragms, and slow-moving water pathways can become ideal breeding grounds for opportunistic waterborne pathogens.

This is not a theoretical concern. Groundbreaking research published in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology found that 50% of electronic faucets tested in a healthcare setting were positive for Legionella, compared to only 15% of manual faucets. The slower flow rates and internal complexity were identified as contributing factors. This evidence suggests that from an infection control standpoint, the perceived benefit of a touchless interface may be negated by the increased risk of aerosolizing contaminated water directly onto a user’s hands.

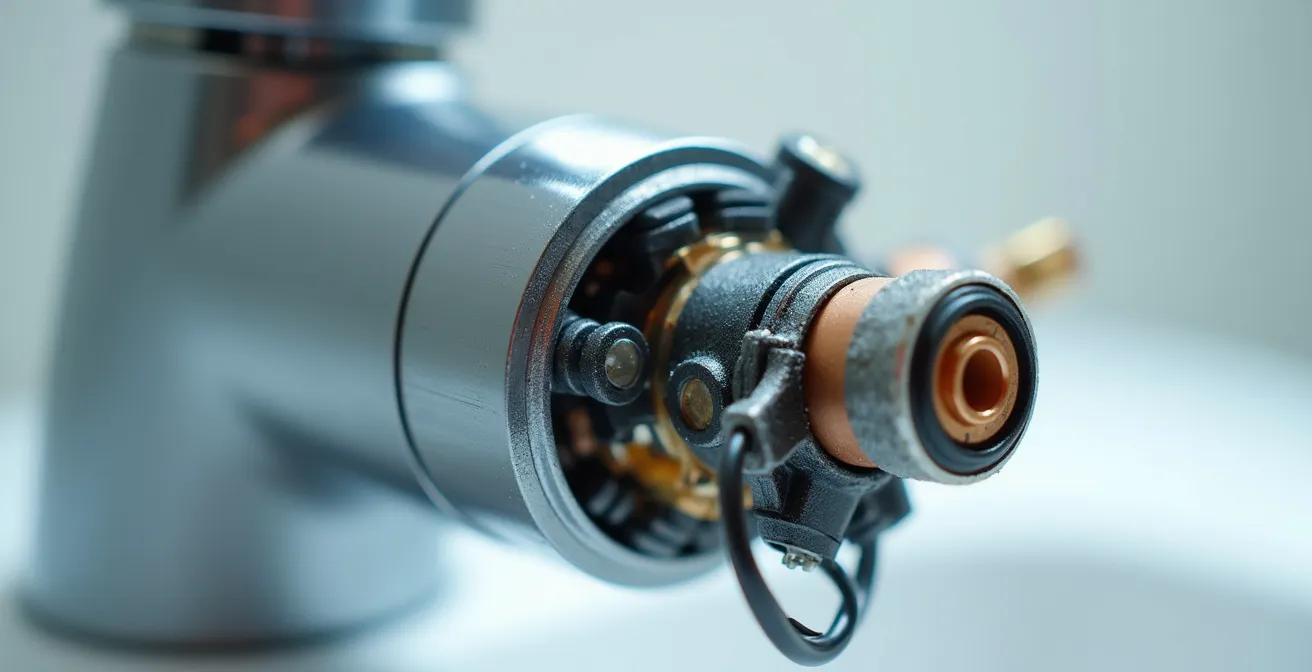

As the image above illustrates, the internal mechanisms of an electronic faucet are far more complex than a traditional manual fixture. Each component—from the sensor to the valve—represents a potential point of failure and a surface for biofilm accumulation. For a maintenance department, this translates into a more challenging and costly service regimen compared to simpler, more robust manual faucets.

Case Study: Johns Hopkins Hospital Reverts to Manual Faucets

After a 2009 study revealed higher Legionella contamination rates in their hands-free electronic faucets, Johns Hopkins Hospital took decisive action. The institution removed the initial 20 electronic faucets from patient care areas and replaced them with traditional manual models. Based on this evidence, the hospital proceeded to replace 100 similar electronic faucets throughout the facility. For its new clinical buildings, it specified 1,080 manual fixtures, explicitly prioritizing evidence-based infection control over the convenience of touch-free technology.

For critical environments like hospitals, the proven reliability and lower contamination risk of a well-maintained manual faucet may represent a more strategic choice for long-term patient safety.

How to Organize a Maintenance Plan for 200 Bathrooms Without Blowing the Budget?

Managing maintenance for hundreds of bathrooms in a public institution is a formidable logistical and financial challenge. The key to success is shifting from a reactive “fix-it-when-it-breaks” model to a proactive, data-driven preventive maintenance (PM) program. This is especially critical in Quebec’s current fiscal climate, where public institutions face significant financial pressures. With recent reporting revealing that 60% budget cuts imposed on CEGEPs have left many schools in critical condition, an unmanaged maintenance plan is a direct threat to an institution’s operational viability.

A strategic plan begins with a comprehensive inventory and risk assessment. Each fixture, valve, and drain is cataloged and assigned a criticality rating. A leaking faucet in a storage closet is a low priority; a malfunctioning backflow preventer on a main water line is a high-priority emergency. This allows you to focus resources where the risk of failure would have the most severe consequences for health, safety, or operational continuity. The plan must then clearly delineate tasks between in-house janitorial staff and licensed professionals.

The Régie du bâtiment du Québec (RBQ) and the CMMTQ have strict rules about who can perform certain plumbing tasks. Simple surface cleaning can be handled by janitorial staff, but any work that involves opening a drain, servicing a valve, or testing a safety device requires a certified master plumber. Misallocating these tasks not only violates the code but also creates significant liability and can void insurance coverage. A well-structured plan respects these legal boundaries, optimizing the use of costly professional services for tasks that genuinely require their expertise.

The following table, based on guidelines from the RBQ, provides a clear framework for allocating maintenance responsibilities. This division of labor is fundamental to creating a cost-effective and compliant program.

| Task Type | Can be done by janitorial staff | Requires CMMTQ certified plumber | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface cleaning & disinfection | Yes | No | Daily |

| Trap cleaning | No | Yes | Quarterly |

| Valve exercising | No | Yes | Semi-annual |

| Backflow preventer testing | No | Yes | Annual (mandatory) |

| Fixture replacement | No | Yes | As needed |

This transforms the maintenance budget from a reactive cost center into a strategic tool for ensuring long-term institutional resilience and safety.

Universal Bathrooms: The Design Flaws That Lead to Non-Compliance

Achieving true universal accessibility is more complex than simply installing grab bars and a raised toilet. In Quebec, compliance is governed by the Quebec Construction Code, which incorporates and often exceeds the standards of the National Building Code of Canada. A common and costly mistake for facility managers is assuming that meeting the national standard is sufficient. Quebec has specific, stricter requirements that, if overlooked, can render a newly renovated or constructed bathroom non-compliant, leading to expensive retrofits and potential legal challenges.

The devil is in the details. For example, while the national code may specify a certain door width, Quebec often demands more generous clearances to better accommodate modern mobility devices. Similarly, the force required to operate a door, the placement and load-bearing capacity of grab bars, and the turning radius within the stall are all specified with precise metrics that must be adhered to. A failure to provide a 915mm clear door opening, or installing grab bars that cannot support the mandated 1.3kN of force, are not minor oversights; they are fundamental compliance failures.

Another area prone to error is the selection and placement of fixtures. The clear floor space required around the toilet, the height of the sink, and the type of faucet controls are all non-negotiable elements. Using a vanity cabinet that obstructs knee space for a wheelchair user or choosing lever-handle faucets instead of hands-free or paddle-style controls can make the space unusable for some individuals. In healthcare settings, the requirement for automatic door operators on all universal washrooms serving patients is another Quebec-specific mandate that is often missed in projects managed by firms unfamiliar with the local code.

Ensuring compliance requires a proactive, detail-oriented approach from the earliest design stages. It involves working with architects and contractors who have demonstrated expertise specifically with Chapter III of the Quebec Construction Code and its accessibility provisions (CSA B651). Verifying every dimension, specification, and product choice against these local requirements is the only way to avoid the costly and disruptive process of remediation after the project is complete.

This diligence is not just about following rules; it’s about providing genuine dignity and access to all members of the community your institution serves.

Hospital Water Outages: The Vital Protocol to Avoid Impacting Patient Care

In a hospital, a water outage is not an inconvenience; it is a full-blown clinical emergency. Water is essential for everything from hand hygiene and sterile processing to dialysis and basic patient care. A sudden or poorly managed shutdown can have catastrophic consequences. For this reason, Quebec’s Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux (MSSS) and the RBQ mandate a rigorous protocol for both planned and unplanned water service interruptions in healthcare facilities. The core principle is operational continuity, ensuring that patient care is never compromised.

For any planned shutdown, the protocol begins with extensive communication. The hospital must notify the regional MSSS coordinator at least 48 hours in advance. Internally, this triggers the activation of the hospital’s incident command system, the same structure used to manage mass casualty events. This team is responsible for coordinating every aspect of the shutdown, from deploying temporary water supplies to communicating with clinical department heads. The goal is to ensure that critical areas like the emergency room, intensive care units, and operating theaters have an uninterrupted supply of potable water.

The logistical effort is immense. It involves deploying large, temporary water storage systems, often mobile tanks coupled with RBQ-approved booster pumps to maintain adequate pressure throughout the facility. Specific patient care continuity measures must be implemented; this might include temporarily switching to single-use sterile instrument kits, using bottled water for patient hydration, and stocking up on alcohol-based hand sanitizer. Every department must have a clear plan for functioning without its primary water source.

The protocol does not end when the water is turned back on. The final, critical step is a comprehensive water quality testing regimen. After any significant disruption to the system, there is a risk of contamination. The post-shutdown protocol requires flushing all lines and conducting rigorous testing for bacteria like Legionella and E. coli, as mandated by public health authorities. Only after receiving clear test results can the water system be declared safe for clinical use. This multi-stage process is vital to upholding the highest standards of patient safety.

This meticulous planning is what stands between a manageable operational event and a potential public health disaster.

Round vs. Square-Bottom Drains: Which Prevents Bacterial Buildup?

In the sterile environments of a hospital’s surgical suite or a school’s science lab, the fight against bacterial contamination extends to the smallest details of facility design. The shape of a floor drain, a seemingly minor choice, can have a significant impact on an institution’s ability to maintain a hygienic environment. The debate between round-bottom and square-bottom drains centers on a simple principle of fluid dynamics: eliminating corners and stagnation points where bacteria can thrive. Square-bottom drains, with their 90-degree angles, create dead zones where water flow is minimal, allowing debris and microorganisms to accumulate and form resilient biofilms.

Round-bottom or radiused-corner drains, by contrast, are engineered to promote complete evacuation. The curved surface facilitates a more efficient flow, helping to flush away contaminants and preventing them from settling. This design principle is recognized as a best practice in sanitary design and is a key consideration for hygiene inspectors. According to special requirements for healthcare plumbing outlined by organizations like the CSA Group, the material and finish of the drain are just as important as its shape. In critical care areas of Quebec hospitals, standards often call for 316L stainless steel with an electropolished finish, a combination that provides superior corrosion resistance and an ultra-smooth surface that further inhibits bacterial adhesion.

The preference of MSSS hygiene inspectors for round-bottom designs in critical healthcare settings is not arbitrary; it’s based on the clear advantage these drains offer in facilitating effective cleaning and reducing the risk of harboring pathogens. While a square drain might be slightly cheaper or easier to install, the long-term cost of battling persistent contamination and the associated risks far outweigh any initial savings. For a facility manager, specifying a round-bottom drain is a proactive measure that contributes directly to the institution’s infection control program.

This choice exemplifies the principle of “sanitary by design.” It’s about engineering a facility where hygiene is inherent in the infrastructure itself, rather than being solely dependent on the diligence of cleaning protocols. This small detail can have an outsized impact on safety and operational integrity.

In environments where cleanliness is non-negotiable, even the most basic components must be selected with microbiological consequences in mind.

Water Velocity: Why Does Type L Copper Better Resist Turbulence Erosion?

In large institutional buildings with extensive plumbing networks, water doesn’t just flow; it races. Hot water recirculation systems, designed to provide instant hot water at fixtures far from the water heater, keep water moving constantly. This constant motion, combined with high velocities and frequent changes in direction at elbows and fittings, creates turbulence. This turbulence can physically scour the inside of copper pipes, a process known as erosion-corrosion. Over time, this can thin the pipe walls, leading to pinhole leaks and catastrophic failures. The choice of copper pipe type is therefore a critical defense against this relentless force.

The Quebec Construction Code, mirroring the National Plumbing Code, specifies three main types of rigid copper pipe: Type M, Type L, and Type K, distinguished by their wall thickness. Type M, the thinnest, is generally suitable for standard residential applications but is ill-equipped to handle the high velocities and pressures of an institutional recirculation system. Type L, with its significantly thicker wall, offers substantially better resistance to erosion-corrosion. For this reason, the code is unequivocal: Type L copper is mandatory for all hot water recirculation lines in commercial and institutional buildings in Quebec.

The local context adds another layer of complexity. As the Régie du bâtiment du Québec highlights, certain municipal water treatments can accelerate this process.

The specific water treatment processes used in major cities like Montreal (ozonation) can accelerate erosion-corrosion in copper pipes.

– Régie du bâtiment du Québec, Quebec Construction Code Chapter III – Plumbing Requirements

This makes the robust wall of Type L pipe not just a good practice, but an essential specification for long-term durability in these regions. The higher initial cost of Type L is a sound investment when weighed against the enormous cost and disruption of repairing leaks inside finished walls years down the line.

The following table provides a clear comparison of the copper pipe types, illustrating why Type L represents the required standard for institutional systems focused on longevity and risk mitigation.

| Pipe Type | Wall Thickness | Max Velocity | Required for Hot Water Recirculation | Cost Premium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type M | 0.025-0.042 inches | 4 fps | No | Baseline |

| Type L | 0.030-0.045 inches | 8 fps | Yes (mandatory) | +15-20% |

| Type K | 0.035-0.065 inches | 10 fps | Optional | +30-40% |

Choosing Type L copper is not about over-engineering; it’s about making a calculated decision to ensure the long-term structural integrity of the building’s circulatory system.

Key takeaways

- System longevity depends on choosing materials like Type L copper that exceed minimum standards to handle the specific operational stresses of institutional environments.

- True hygiene goes beyond surface cleaning; it requires engineering choices, like round-bottom drains, that inherently reduce bacterial harbourage points.

- A proactive, risk-based maintenance plan that respects CMMTQ certification requirements is more cost-effective and safer than a reactive repair model.

What Are the Plumbing Requirements for Food Processing Plants in Quebec?

While sharing some principles with hospitals and schools, food processing plants in Quebec operate under an even more stringent and overlapping regulatory framework. Here, plumbing is not just about sanitation; it’s a critical control point in food safety, jointly regulated by the RBQ and the Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec (MAPAQ). The primary objective is to prevent any possibility of contamination of the food supply, which demands a multi-layered approach to backflow prevention, waste management, and water quality.

The absolute non-negotiable in a food plant is backflow prevention. Any connection where potable water could potentially come into contact with non-potable substances (e.g., cleaning chemicals, processing fluids) is considered a high-hazard point. At these connections, the code mandates the installation of a Reduced Pressure Principle Assembly (RPBA). This is the most robust form of backflow protection available, and its annual testing and certification by a licensed professional is mandatory, with reports often required by both the RBQ and MAPAQ.

Wastewater discharge is another area of intense scrutiny. Plant effluent often contains high concentrations of fats, oils, and grease (FOG), as well as organic solids. To protect municipal sewer systems, facilities must install and maintain properly-sized FOG interceptors. Furthermore, discharge is subject to strict temperature and pH limits. Municipal bylaws typically cap effluent temperature at 60°C to prevent damage to sewer infrastructure, and pH levels must be monitored and maintained within a neutral range (commonly 5.5-9.5) to avoid corrosion. These parameters are not just guidelines; they are enforceable regulations that carry significant financial penalties if violated, on top of high water costs, where current commercial water rates show a price of $1.737 per cubic meter in major Quebec cities.

Compliance in a food processing environment requires a comprehensive system of checks and balances. Key compliance actions include:

- Installing RPBA backflow preventers at all high-hazard connection points.

- Verifying and respecting municipal water discharge temperature limits (typically max 60°C).

- Implementing and regularly servicing FOG interceptors that meet local specifications.

- Ensuring pH monitoring systems actively maintain effluent within the required 5.5-9.5 range.

- Submitting annual backflow prevention test reports to both the RBQ and MAPAQ as required.

For a food processing facility, the plumbing system is an integral part of the HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) plan. Proactive management and meticulous documentation are essential for ensuring food safety and avoiding costly regulatory actions.

Frequently Asked Questions About Quebec’s Institutional Plumbing Standards

What is the minimum door clearance required in Quebec for universal bathrooms?

Quebec requires a 915mm clear door opening width, which is more stringent and provides better access than the 810mm national standard.

Are automatic door operators mandatory in Quebec hospitals?

Yes, for all universal washrooms in healthcare facilities that serve patients with mobility impairments, automatic door operators are a mandatory requirement under the Quebec code.

What are the grab bar requirements specific to Quebec?

In Quebec, grab bars must be capable of supporting a force of 1.3kN and must be positioned according to the CSA B651 standard, as adopted and enforced by the province.